Friday, 1 October 2010

IN FOREIGN FIELDS E-BOOK

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Foreign-Fields-Heroes-Afghanistan-Their/dp/1906308071/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1285927439&sr=1-1

Tuesday, 2 September 2008

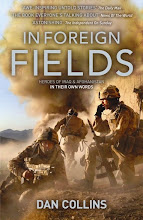

IN FOREIGN FIELDS

In Foreign Fields is a compilation of 25 gripping, astonishing and moving interviews with British medal winners from Iraq and Afghanistan.

They charged through ambushes, fought pitched battles which left dozens dead, saved injured comrades and rarely took a backwards step.

Now they tell their own stories, in their own words.

Of the interviewees, twenty are soldiers, three are Royal Marines and two are serving with the RAF. One is female.

Ten won the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross - the medal just below the Victoria Cross. Others won Military Crosses, one the Distinguished Flying Cross and one the Distinguished Service Order.

The book is not about the politics of either war; it is simply about the experiences of those, on the British side, who found themselves involved.

Each 'chapter' begins with a few introductory paragraphs; after that, the medal winners themselves tell their stories, in their own words.

They are, collectively, the most impressive group of people I have ever had the pleasure and privilege of meeting.

Below you will find each of the introductory paragraphs and, at the very end, my foreword.

To buy In Foreign Fields, go here, or here, or to any good bookshop.

Please feel free to comment at the bottom.

Dan Collins.

LIEUTENANT CHARLES CAMPBELL, MILITARY CROSS

THE ROYAL REGIMENT OF FUSILIERS

WHEN Coalition Forces finally invaded Iraq on March 20, 2003, the men of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers were among the first across the border. Among the first of the Fusiliers was Charles Campbell, a quiet and modest man with a broad smile and a hint of the Zambia of his youth in his accent. Campbell was 7 Platoon commander with Y Company of the First Fusiliers Battlegroup during Operation Telic One.

The day after the invasion, his platoon was ordered to secure a strategically important motorway bridge over the Shatt-Al-Basra waterway outside Basra, Iraq’s second biggest city. Campbell led a dawn attack, his men fighting their way across the bridge on foot – armoured vehicles could not cross because it had not been cleared of explosives. With mortars landing all around them, and machine gun rounds and rocket propelled grenades filling the air, they pressed home the attack against an enemy dug in on the far bank in good positions. Despite the odds being stacked against them, Campbell’s light force got across and took prisoners. His citation says he “pressed home his attack, inspiring his troops by personal example, displaying no concern for his own personal safety.”

The following two days and nights saw Lt Campbell and his men fight off near-continuous enemy assaults, while under mortar fire for at least 30 of those 48 hours. He “stayed calm and self-assured in command and…his men were able to repulse at least three well-organised and fierce attempts by the enemy to dislodge his small force from the eastern bank.”

On the night of 27 March 2003, Campbell led an assault force deep behind well-prepared enemy lines, showing ‘considerable courage and determination in the face of great personal danger’ as his men sought enemy prisoners.

LIEUTENANT CHRIS HEAD, MC

THE ROYAL REGIMENT OF FUSILIERS

AS Charles Campbell and the men of 7 Platoon, Y Coy were assaulting their bridge, Chris Head and 10 Platoon of Z Coy were tasked with taking and holding another strategically vital bridge some three or four kilometres to the east.

Head, a friendly and engaging man with a self-deprecating air, watched as others raced ahead of him on the opening day of the war, resigned never to seeing any action.

But before long he found himself in a similar situation to Campbell.

He and his men arrived at their bridge expecting to find it taken by an American tank unit who had arrived some time before. In fact, lacking the infantry support essential to the task, they had been beaten back. Head and his men stepped up to have a go and the succeeded where the US forces had failed, Head leading his platoon in what his citation describes as “a devastating dismounted attack on enemy positions, including revetted tanks, anti-tank guns and dug-in infantry.”

As with Campbell’s position, the Iraqi Army launched a series of counter attacks; Head “reacted swiftly and aggressively, always to the fore of a robust defence and constantly in range of the enemy’s weapons. He showed courage under fire, determination and inspirational leadership throughout the fierce and unrelenting engagement, motivating and inspiring his men for many hours; his selfless courage belied his age and experience.”

SERGEANT MARK HELEY, MC

CORPS OF ROYAL ENGINEERS

AS the Fusiliers were working to secure the area around Basra, other forces were pushing further north.

Among them was Mark Heley, a, experienced Patrol Commander in the Reconnaissance Troop of 23 Regiment (Air Assault).

His job – with his team – was to provide engineer-based intelligence for 16 Air Assault Brigade. Sgt Heley and his patrol were mounted in un-armoured, stripped down ‘WMIK’ Land Rovers, and operated well in advance of the main body of the Brigade throughout the ground war. Of the 21 days of hostilities, there was only one day when he and his patrol were not ‘danger close’ to the enemy and they often found themselves miles from friendly forces.

On March 23, on a joint patrol with the Brigade’s Pathfinder Platoon, Heley and his team became cut off from the Brigade 40 kilometres behind enemy lines. They had been sent north to check out an airfield which was being touted as a possible drop zone for soldiers from the Parachute Regiment. Advancing beyond Coalition lines – where US Marines and the US Army were stuck in very heavy fighting – they hit the road.

It was dark, and almost immediately they were ambushed in a carefully-prepared killing ground. It turned out to be the first of many such traps they would drive through. Astonishingly, no-one was injured, but eventually it became clear that heavily-armed enemy forces were now out hunting them. As they approached a village where the Iraqis were preparing a huge final ambush – which would likely have been a death-trap – Heley and his colleagues pulled off the road into the pitch black desert. They watched a convoy of heavily-armed Iraqis race by; trapped, they realised their only option was to fight their way back south; in their path, the same ambush killing grounds they had already battled through.

LIEUTENANT SIMON FAREBROTHER, MC

1st THE QUEEN’S DRAGOON GUARDS

A WEEK after Mark Heley’s exploits, British forces were still involved in fighting their way north to Basra, Iraq’s second city. Simon Farebrother, 2nd Troop leader, C Squadron Queen’s Dragoon Guards, was working with the Brigade Recce Force and 40 Commando to clear Route 6, the main highway.

In their way stood Abu Al Khasib, a small town which was, effectively, a suburb of Basra. Farebrother’s troop was ordered to seize a bridge to the east of the town to secure lines of communication and divert the enemy from the main axis of 40 Commando’s attack, which was to come from the south.

In the early hours of 30 March, approaching the bridge in the dark, the BRF were engaged with RPGs and small arms, so Farebrother immediately pulled forward to give fire support into a bunker at a range of only 50 metres with his 30mm. The position suppressed, Farebrother and Cpl Armstrong, the commander of the other vehicle in his section, then crossed the bridge and began to put down suppressive fire on buildings on the far bank with 30mm and 7.62mm.

Just as it appeared that things had quietened down, an RPG was fired at short range at Cpl Armstrong, exploding on the Tarmac a metre short of his hull. He reversed but in so doing ended up in a ditch and threw a track. The section therefore found themselves immobilised and isolated on the enemy bank, with the sun rising and exposing the two vehicles to more enemy fire.

LANCE CORPORAL JUSTIN THOMAS, CONSPICUOUS GALLANTRY CROSS

ROYAL MARINES

WITH others like Simon Farebrother and his men working to clear the area around Abu Al Khasib and secure bridges and other strategically important sites, the Royal Marines, supported by Challenger 2 tanks and Scimitars, were launching Operation JAMES. Named after James Bond, this involved 1,000 men and was designed to trap an Iraqi force of up to 3,000 who were well dug-in in the streets and houses of the suburb.

Justin Thomas, a GPMG section commander in Manoeuvre Support Group of 40 Commando, was among the ‘Bootnecks’ taking part in the operation.

A wiry Welshman with what one Royal Marine officer described as ‘the levelest head I’ve ever seen’, Thomas and his colleagues had been choppered in behind enemy lines to help seize oil fields at the start of the invasion.

They’d then fought their way across the country to the outskirts of Basra – when they suddenly found themselves surrounded and outnumbered in a built-up area.

CORPORAL OF HORSE GLYNN BELL, MC

THE BLUES AND ROYALS

WITH the war won, the Coalition forces set about mounting a peacekeeping operation. For Glynn Bell, a Scimitar Commander in the Blues and Royals, the invasion and the subsequent fighting had been relatively quiet – he had scarcely fired a shot in anger. (His Squadron, though, had suffered a pair of tragedies, with the deaths of LCpl Karl Shearer and Lt Alexander Tweedie in an overturned vehicle and, infamously, that of LCoH Matty Hull, 25, in a so-called ‘friendly fire’ incident.)

On June 24, 2003, however, that changed for the worse. Two sections from 1st Battalion the Parachute Regiment were patrolling in the town of Al Majar Al Kabir, some 250 miles south of Baghdad, when they came under attack. Separated, low on ammunition, pinned down and surrounded by hundreds of armed men, they found themselves in a desperate battle for their lives.

CoH Bell’s troop was tasked to deploy as part of a larger Battlegroup Quick Reaction Force to extract the Paras. As they entered the town, 200 people began firing at them from all directions, with rifles, heavy machine guns and RPGs. Undeterred, Bell and his men pressed forward, supported by a Para multiple which was also trying to fight its way back into the town.

Waiting for them were 200 armed men and a barrage of RPGs and bullets.

CORPORAL SHAUN JARDINE, CGC

KING’S OWN SCOTTISH BORDERERS

SIX weeks after the horrific murders of the six RMPs in Al Majar Al Kabir - and after Glynn Bell and his colleagues had helped the men of 1 Para to escape from a mob in the town – Shaun Jardine was commanding a fire team employed as the Immediate Quick Reaction Force for the Al Uzayr Security Force Base, not far away in Maysan Province.

Shy, skinny and softly-spoken, the young Scot was nevertheless an experienced NCO, having joined the Army as a boy soldier. The Security Force base was a small outpost in the village of Al Uzayr, a Shia backwater halfway between Basra and Al Amarah and the final resting place of the Hebrew prophet Ezra, also revered by Muslims.

On the morning of Saturday August 9, the men were busying themselves, some cleaning their weapons, others on guard duty or eating breakfast, when a huge firefight suddenly broke out 300 metres north of their position. They could hear a prolonged and intense mix of heavy machine gun and small arms fire, and Jardine and his team immediately deployed to investigate.

Almost as soon as they left the compound, they were engaged by two enemy positions 100 metres to the west; at the same time, other elements of the Al Uzayr Multiple, which had also deployed, came under fire to the south.

Pinned down, with no reinforcements available and with his team’s position becoming untenable, Jardine’s citation describes how he took the offensive, charging straight at the blazing enemy guns.

LANCE CORPORAL CHRISTOPHER BALMFORTH

THE QUEEN’S ROYAL HUSSARS

THE following year, the Queen’s Royal Hussars were out in Iraq. Among their number was Chris Balmforth, a rugby-mad junior NCO from the Midlands. The country had been reasonably calm for some time, but on April 4, 2004, a prominent supporter of the maverick Shia cleric Moqtadar al Sadr was arrested. Violence exploded on the streets of southern Iraq to a level not seen since the invasion 12 months previously. Well-armed insurgents repeatedly attacked Coalition Forces with rocket launchers, anti-tank weapons, grenades and machine guns.

Four days into the uprising, LCpl Balmforth was providing top cover to the first of four Land Rovers which were leaving the city’s Al Jameat Police Station, where they had been training members of the Iraqi Police Service.

As the vehicle turned a corner, it was met by concentrated fire from five gunmen armed with machine guns and rocket launchers. At a range of around 15 metres this proved to be devastating: the driver was shot through both his thighs, and his ankle was shattered, and the vehicle was seriously damaged. From a position of top cover Balmforth returned fire immediately, buying time for his colleagues.

MAJOR JUSTIN FEATHERSTONE, MC

THE PRINCESS OF WALES’S ROYAL REGIMENT

JUSTIN Featherstone’s Y Company was located in Cimic House, Al Amarah, in Iraq’s Maysan province, between April and September 2004. Cimic House was the headquarters of the Civilian Military Co-ordination team in the area, which had been relatively peaceful despite some incidents such as those involving 1 Para and the Red Caps at nearby Al Majar Al Kabir the previous year.

However, 1PWRR’s arrival to replace The Light Infantry coincided with the Mahdi Army uprising, which had sparked the violence that saw the ambush on Chris Balmforth’s Land Rover.

Attacks against Coalition forces increased by one thousand per cent and Cimic House, a small and isolated compound, was surrounded and cut off. Re-supply was difficult and dangerous; one attempt to do so resulted in six casualties to the company and those forces attempting to re-supply them. In the space of 16 weeks, the compound was subjected to over two hundred indirect fire attacks from mortars and rockets, and the base sangars were repeatedly hit with short range RPG and small arms fire.

Featherstone – described by soldiers who served under him variously as ‘a legend’, ‘completely mad’ and ‘a man you’d follow anywhere’ – is something of an adrenaline junkie, who has led dozens of Army mountaineering and white water rafting trips. So it’s no surprise that he personally led a large number of night-fighting patrols into the heart of the town’s Mahdi Militia-controlled estates, taking his dismounted troops though the warren of poorly-lit buildings, across dangerously open waste ground and even over rooftops to find and kill the enemy.

They found themselves in firefights virtually every day, facing RPGs, heavy machine guns, small arms, IEDs and snipers, often in combination. Featherstone’s citation explains how, “while under this heavy weight of incoming enemy fire, he would calmly direct his troops and return fire himself, and lead rapid and aggressive follow-ups, often in the face of heavy enemy resistance. This repeatedly brave personal leadership saw his company seize a number of heavy weapons, mortars and numerous rocket-propelled grenades and kill a number of the enemy forces. Featherstone showed personal courage, inspirational leadership, calmness, professionalism, determination and endurance over a protracted period.”

WARRANT OFFICER CLASS 2 MARK EVANS, MC

THE ROYAL WELCH FUSILIERS

WITH the violent Mahdi uprising underway, British forces – such as Justin Featherstone’s troops in Cimic House – were coming under regular and fierce attack.

The men of 1st Battalion The Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment battle group hatched a plan to strike back, with a major night-time search-and-arrest operation codenamed PIMLICO. It was carried out in the maze of narrow streets and alleyways which made up the city’s south-western housing estates in the early hours of April 30, and was aimed at arresting insurgents and confiscating their weapons, ammunition and bombs.

Mark Evans, a father of three from Rhyl with a modest, matter-of-fact air, was tasked with coordinating the arrests, moving prisoners and the exploitation of the search – a “complex and difficult task in a hostile environment” which he carried out “with huge professionalism and great skill”.

At first, the Operation went very smoothly; in pitch black conditions, the soldiers moved almost noiselessly through the streets and broke into a number of target buildings, arresting known terrorists and seizing arms.

However, at first light – just as they reached the final target and uncovered a major cache – the enemy forces realised the British were in their midst.

SERGEANT CHRIS BROOME, CGC

THE PRINCESS OF WALES’S ROYAL REGIMENT

SOUTHERN Iraq was now a very dangerous place to be, and the men of the 1st Battalion The Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment were coming under relentless attack.

Chris Broome was a senior NCO in the Regiment, a Warrior commander with 17 years’ service whom many junior soldiers looked up to – despite the fact that, as he himself says, his own experience of being under fire to that point was non-existent.

Sgt Broome’s job was to resupply the beleaguered Cimic House in Al Amarah, where Maj Justin Featherstone and his troops were under siege, surrounded by suicidal Mahdi Army fighters. Convoys were repeatedly attacked by the insurgents; Pte Johnson Beharry won his Victoria Cross for his work on such missions, and it was Broome who cradled the seriously injured soldier in his arms after he was almost killed by a rocket propelled grenade.

It’s commonly accepted that all the men of 1PWRR fought like the ‘Tigers’ they are, but one platoon, says the citation, had the hardest time of all: that platoon was Chris Broome’s, and he was always to be found at their forefront, repeatedly putting his own life in grave danger to save those of his men.

He “demonstrated gallantry, leadership and courage far beyond that reasonably expected of one in his position,” the citation adds, “fighting the enemy from his Warrior and on foot… He led his men with courage and valour and his selfless, modest approach has been an inspiration to his men, his peers and his superiors.”

Sgt Broome's Conspicuous Gallantry Cross was awarded for a series of actions, each of staggering bravery.

LANCE CORPORAL DARREN DICKSON, MC

THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS, TERRITORIAL ARMY

ALTHOUGH the situation was certainly worse further north in Maysan Province, British soldiers in Basra were coming under fire increasingly often.

Darren Dickson was a young bus driver from Edinburgh with plans to enter the priesthood; he was also a lance corporal in the Territorial Army. On May 8 – as Chris Broome and his colleagues in 1PWRR were mounting Operation WATERLOO up in Al Amarah – Dickson was in the top cover sentry role in an open Land Rover which was part of a 1 Cheshire Battle Group detail escorting a convoy of Low Mobility Water Tankers through the southern city.

At just after 6.30am, they were ambushed with a combined IED, RPG and small arms attack, and 22-year-old Dickson – who had only arrived in Iraq a week earlier – suddenly found himself fighting for his life.

SERGEANT TERRY BRYAN, CGC

ROYAL HORSE ARTILLERY

AS spring turned to summer and the blistering heat of August set in, the mood on the streets of Basra became darker still, just as it was doing further north.

At around 3pm on August 9, a small group of soldiers found themselves stuck in a satellite base a short distance away from the main UK camp in the city. They were surrounded by an increasingly volatile crowd, and fears grew for their safety. Eventually, it was decided to send other troops out to cover their extraction.

Terry Bryan led a two multiple patrol to help bring the men in.

However, before they reached their destination, they drove into a clever and carefully-planned ambush.

So began a nightmare ordeal that saw their vehicles destroyed by an enormous weight of rocket propelled grenades and machine gun fire; Sgt Bryan and his RHA multiples were forced onto unfamiliar streets and into a running battle with hordes of insurgents.

Desperate, they broke into a building; surrounded, and shooting attackers at point blank range to keep them at bay, their ammunition started running dangerously low.

A quick reaction force was sent out to rescue them but, with communications patchy, and the enemy now trying to set the building alight, Bryan and his men, some of them teenagers, began to fear the worst.

CORPORAL TERRY THOMSON, CGC

THE PRINCESS OF WALES'S ROYAL REGIMENT

WITH Terry Bryan’s ill-fated patrol scrapping for their lives, the Quick Reaction Force of Warriors from 1 PWRR was leaving to rescue them.

Terry Thomson was commanding one of the Warriors in the QRF. He and his colleagues knew that they would be hit hard almost from the moment they left their base – and they were not disappointed: hundreds of Mahdi Army militiamen were lying in wait for them.

What followed was among the most heroic actions in the history of British involvement in Iraq, as the QRF fought its way to the area where the stranded soldiers were thought to be.

Dozens of rocket propelled grenades and thousands of rounds were fired at them and Cpl Thomson’s Warrior suffered severe damage which rendered his radio system inoperable. As a result, he had to fight his vehicle from the turret, surrounded by gunmen firing at him from alleyways, roofs and windows.

Finally, he arrived at the RHA coordinates - only to find they were not there.

COLOUR SERGEANT MATT TOMLINSON, CGC

ROYAL MARINES

AS their British allies fought the insurgency in the south of Iraq, American forces were engaged in fighting of their own further north. Some of the fiercest battles were in the so-called ‘Sunni Triangle’ – a huge area stretching from Baghdad in the east to Tikrit in the north and Ramadi in the west. At the bottom of this triangle was the city of Fallujah.

American soldiers had shot dead a number of demonstrators in the city in April 2003, and the following year a terrible revenge had been extracted on four US contractors who had been dragged from their car in the city. A mob had battered the men to death, set their bodies on fire and strung the remains up from a bridge.

After that, the area had become something of a no-go zone for Coalition forces until, in November 2004, the US Marines mounted a huge operation to retake the city from insurgents. It turned out to be the largest land battle since the Tet offensive during the Vietnam War.

Matt Tomlinson, a British Royal Marine NCO, was attached to the USMC – and delighted to be allowed to go into action with his comrades.

Once in Iraq, he found himself passing on invaluable ‘small boat’ skills to the Americans as they patrolled the Euphrates river, seeking to intercept enemy forces and weapons coming in and out of the city.

On November 15, his team were ambushed by insurgents in well-prepared positions on the river bank. As heavy machine gun fire, AK47 rounds and RPGs rained down on their boats, Tomlinson’s natural instinct would have been to try to flee.

Instead, he pointed the craft straight at the attackers, jumped ashore and ran towards the fire.

CAPTAIN SIMON BRATCHER, MC

THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS

THE Iraqi insurgents and militia gunmen have always come off second best in firefights with British forces, whose superior training, tactics and discipline enabled them to win against apparently overwhelming odds on many occasions. However, there is one weapon in the terrorist arsenal that tips the balance the other way – the Improvised Explosive Device, or roadside bomb.

These have proved devastating against British armoured vehicles, with tragic consequences.

Frequently – through skill, intelligence or luck – IEDs are found before they can be detonated. When this happens, men like Simon Bratcher are called to the scene to defuse them. This is an incredibly dangerous job which requires huge bravery, great skill and very steady hands.

Talking on a sunny, spring morning in Oxfordshire, Bratcher – a quietly-spoken and extremely modest man – seemed a million miles away from the heat and dust of the Iraqi roadside where he found himself on Monday June 6, 2005.

A patrol had reported a suspicious object – ‘some wires and an antenna’ – and he had deployed to the area, intending a rapid remote render-safe of the device. But the IED waiting for him was out of the ordinary – a massive, highly sophisticated victim-operated bomb. He could have destroyed it. But he decided to risk his own life to recover it intact, to allow forensic scientists to look for clues to the maker.

MAJOR JAMES WOODHAM, MC

ROYAL ANGLIAN REGIMENT

ON September 19, 2005, two British soldiers were arrested by Iraqi police after shots were fired near the infamous Al Jameat police station in Basra. The two men, who had been working on counter-terrorist surveillance, were bundled away to the police station for interrogation.

British troops were quickly on the scene. With elements in the Iraqi police linked to the militias, it was feared that the pair might be passed on to terrorists and either used as bargaining chips for the release of insurgent prisoners or even executed.

But the police refused to release the soldiers, claiming they were Israeli spies, and a mob of angry Iraqis began forming outside.

Petrol bombs were thrown – one setting a sergeant on fire in pictures that were beamed around the world – and then shots, RPGs and anti-tank missiles were fired.

James Woodham, a married man from Norwich and now a lieutenant colonel, was a major at the time; he had good links to the Iraqi Police, so he was called to the Al Jameat to try to negotiate the release.

He and his team found themselves trapped inside the building, with the atmosphere rapidly deteriorating and turning very ugly.

COLOUR SERGEANT JAMES HARKESS, CGC

THE PRINCESS OF WALES’S ROYAL REGIMENT

IN 2004, The Princes of Wales’s Royal Regiment had clashed with the militiamen of Mahdi Army in some of the fiercest and most brutal fighting the British Army had seen in modern times.

Jim Harkess, a Platoon Warrior Sergeant in C Company, 1 PWRR, had been on that tour, and had also been in Iraq, attached to the Royal Regiment of Wales, the year before.

In 2006, Harkess found himself back out there for the third time, deployed with the Queen’s Royal Hussars Battle Group in Al Amarah on Operation TELIC 8.

Like Chris Broome before him, CSgt Harkess, a Nottinghamshire miner who had joined the Army after the pit closures of the 1980s, was later awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross for “bravery in the face of the enemy” on three separate occasions. His citation says he “demonstrated immense courage, repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire and led counter attacks, and led his platoon with real bravery, gallantry and leadership.”

PRIVATE MICHELLE NORRIS MC

ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS

WHEN British forces first went into Iraq, Michelle Norris was a schoolgirl. Just three short years later, she was sitting in the back of a Warrior armoured vehicle at the centre of one of the biggest battles British troops fought in Iraq.

It was June 11, 2006, and she and her colleagues were engaged in a night-time search operation aimed at arresting key Mahdi Army figures and seizing their weapons and ammunition. It had erupted into full-on war fighting, with hundreds of enemy fighters surrounding the British troops.

A few hundred metres away, Jim Harkess was engaged in one of the actions which would see him awarded the CGC, and many other soldiers were fighting hard.

Pte Norris was just 19 years of age, and only recently out of basic training. During the heaviest of the fighting, CSgt Ian Page, the commander of her Warrior, was shot in the face and seriously injured.

Without hesitation, Norris dismounted and climbed onto the top of the vehicle to administer life–saving first aid, while under sniper fire and with heavy small arms fire and rocket propelled grenade attacks continuing around her.

WING COMMANDER ‘SAMMY’ SAMPSON, DSO

NUMBER 1 (FIGHTER) SQUADRON, RAF

ALONGSIDE Iraq, Britain’s troops have been heavily involved in Afghanistan.

Sammy Sampson served on two tours of operational duty there between December 2004 and May 2006, flying 103 missions during “high tempo operations, in demanding climatic and environmental conditions”, and in the face of “a significant and hostile level of enemy activity”.

He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for a combination of the way in which he motivated his pilots and ground crew and his own actions in combat.

“Through his inspirational and composed leadership, justifiable pride, impressive self discipline and unreserved application,” says the citation, “Sampson instilled an outstanding level of drive, morale, mission focus and singular determination in each member of his unit.”

FLIGHT LIEUTENANT MATT CARTER, MC

ROYAL AIR FORCE REGIMENT

AS Sammy Sampson’s story shows, air power can be the difference between life and death for troops on the ground in Afghanistan.

It is, of course, vital that the bombs, shells or missiles delivered by the aircraft hit their intended targets; flying several thousand feet up, at high speed and with British troops and Taliban attackers often separated by a matter of metres, the potential for tragic errors is clear. To minimise the risk, specialists are used on the ground to speak to the pilots and ‘talk them on’ to enemy positions.

Matt Carter was one of those specialists – the Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) officer with 3 PARA Battle Group HQ.

This is a dangerous trade; necessarily, the TACP will be near the front of the fighting at all times.

Carter was involved in a number of major contacts, directing “close and accurate fires immediately, without prompting and with devastating results.” His citation adds that, “without regard for his personal safety, he was determined to join the forward line of troops, and gallantly and repeatedly exposed himself, during all contacts with the enemy, to a very high risk of being killed.”

Among the many actions he was involved in, the citation picks out two.

In the first, Carter found himself metres from the Taliban, with himself and his colleagues in grave danger.

In the second, he jumped from a flying helicopter (some 15 feet off the ground), in the pitch black, straight into a huge firefight.

LIEUTENANT HUGO FARMER, CGC

THE PARACHUTE REGIMENT

IN an attempt to push the Taliban back, British troops set up bases in District Centres – government office compounds – in a number of towns in Helmand. One of these was Sangin, a settlement in the north east of the region, below the strategically vital Kajaki Dam. Situated in the middle of the country’s opium fields, and home to around 15,000, it is a typically Afghan collection of dusty, pale yellow, stone-and-mud buildings and narrow, winding alleys.

Hugo Farmer, a young lieutenant with 3 Para, led his men in to the Sangin DC for what was intended to be a whistle-stop visit to extract a wounded local leader. 3 Para ended up spending weeks there, and lost a number of men in the process, including one of their best, Cpl Bryan Budd VC.

They were rocketed and mortared in the DC and ambushed every time they left to go on patrol; Sangin became a byword for savage fighting, danger and death.

Lt Farmer commanded 1 Platoon A Company in some of the most intensive engagements of the tour; he “consistently demonstrated outstanding leadership and gallantry,” says his citation, and regularly “led assaults on enemy positions.”

He won his CGC for several actions, including that on the day Cpl Budd won his posthumous Victoria Cross.

LANCE CORPORAL OF HORSE ANDREW RADFORD, CGC

THE LIFE GUARDS

WHILE Hugo Farmer and his men were fighting the Taliban daily in Sangin, others were engaged in battles of their own in and around the town of Musa Qala to the north west. The administrative centre of the Musa Qala region – a sparsely-populated area made up of many small villages concentrated in the valley cut by the Musa Qala river – had been held for some time by soldiers of the Pathfinders, the elite forward reconnaissance element drawn mainly from the Parachute Regiment.

In scenes reminiscent of Rorke’s Drift, they had fought off wave after wave of Taliban attacks, running desperately low on food and water, before a Danish column had eventually fought their way through to reinforce them.

Now the Pathfinders were being extracted, and a group of Household Cavalry armoured vehicles was sent to assist them.

Andrew Radford, a young father of four from the Potteries, was part of that convoy.

The convoy had reached a village just south of the town on August 1 last year when a huge Taliban bomb exploded, destroying the vehicle in front of LCoH Radford’s.

One of the four men inside was his close friend Ross Nicholls; another vehicle further ahead was now being engaged with rockets and machine gun fire.

Radford was about to perform an act so brave it would earn him the British Army’s second highest decoration.

MAJOR MARK HAMMOND DFC

ROYAL MARINES

WHEN soldiers are hurt, it is to the helicopter pilots that their comrades turn. Injured men need urgent medical assistance and the only way to achieve this is through aerial evacuation. This means – as often as not – landing in a hot ‘LZ’, with enemy fighters blazing away at you with machine guns and RPGs.

It doesn’t take much to imagine how dangerous – and frightening – this would be. Yet at the very moment when the danger is at its greatest, the steadiest of hands and nerves are required.

Mark Hammond is something of a rarity; a Royal Marine Chinook pilot. But his flying – leading the Immediate Response Team (IRT) and Quick Reaction Force for the Operation HERRICK Helmand Task Force, based at Camp Bastion – was in the best traditions of his elite Corps.

Like the other Chinook pilots and crews, and the surgical teams who travelled with them, Maj Hammond regularly put his own life in danger to save the lives of others.

LIEUTENANT TIMOTHY ILLINGWORTH, CGC

THE RIFLES

THE British forces in Afghanistan are only there with the blessing of the country’s government. Ultimately, it will fall to the Afghans themselves to defeat the Taliban and ensure their country’s future. To that end, while our troops have been involved in heavy fighting themselves, the long-term aim is to equip the Afghan police and army to take on the fight.

Tim Illingworth, a young officer with The Rifles, was a member of the Operational Mentoring and Liaison Team working with the local forces to improve their capability.

He had deployed to Afghanistan in April 2006, and quickly fell in love with this wild, rugged country.

On September 10, Lt Illingworth deployed with a small force of OMLT in support of a joint Afghan Police and Army operation to recapture Garmsir District Centre in the face of heavy and continuing resistance. His bravery and example over seven days was well beyond the call of duty. His role was to mentor rather than fight, but he “consistently placed himself in positions of utmost danger. He showed outstanding courage, leadership and selflessness, and such inspiring and raw courage from a relatively young and inexperienced officer is richly deserving of the highest recognition.”

Foreword by Dan Collins

Britain’s twin Middle Eastern campaigns, rightly or wrongly, do not command universal popular support at home.

Whatever your views, however, you must accept that the troops themselves have no say in when and where they fight; to paraphrase Tennyson, theirs is not to reason why, theirs is but to do and, sometimes, die.

In an age where many people seem more interested in football trivia, the latest diets and the next reality TV show than in the deeds of our men and women on the front line, I wanted to give some of those who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan the opportunity to tell their stories, in their own words.

Almost every Briton ‘on the ground’ in those countries will be in harm’s way many times during a tour of duty. Tales of courage, self-sacrifice and dedication to duty abound, and a library would be needed to do them all justice. So I sought out those recognised even within their own fraternity – medal winners.

By its very nature, the military honours system is imperfect. Many outstanding acts go unrewarded, unnoticed in the heat of battle or ‘written up’ unsuccessfully. However, to win the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross, the Military Cross or any of the other awards featured in these pages, you must have performed to a very high level. Many of the men herein – and Pte Michelle Norris MC, the sole woman entry – stood toe-to-toe with death and moved forwards in its face.

That is not say they were ‘gung-ho’ about their actions. Many, of all ranks and ages, had tears in their eyes as they recalled their experiences. A few had struggled emotionally since returning home. None had enjoyed the business of killing, and many showed considerable compassion for those they were fighting. All were profoundly proud of their service and their colleagues, and all expressed an almost identical sentiment which may be summarised thus: This medal is for everyone who was there with me. Any of them would have done what I did..it just happened to be me.

All were selected, at random, by me; the choice of one particular action and individual over others is emphatically not a comment on any award or person. I could have written this book ten times over with entirely different names each time.

I hope it doesn’t sound pompous to say that meeting the 25 interviewees was a moving, rewarding and humbling experience; my own unimpressive and unremarkable life was thrown into uncomfortably sharp relief as I talked to people who had travelled thousands of miles to be mortared and machine-gunned and hardly turned a hair. But strangely, given their uniform bravery and the nature of their exploits, the most impressive feature of the interviewees was their modesty. None had requested to be included; all were recommended by their superiors and all, indeed, required a degree of persuasion. They seemed to me to offer a window into the past, to a Britain of many years ago, before the era of instant celebrity, when a high value was placed on steadfastness and ‘heroes’ were people to respect, rather than millionaire footballers or Hollywood actors. (Incidentally, this book was originally going to be called Heroes; this was dropped after the heroes themselves told me the title would embarrass them.)

In Foreign Fields does not pretend to give an overview of the events in either country, or the wider geopolitics of the Middle East. There are links between some of the chapters – for instance, the Royal Horse Artillery multiple led by Sergeant Terry Bryan CGC were rescued by a Quick Reaction force of the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment which included Corporal Terry Thomson CGC – but, essentially, it is a collection of 25 discrete incidents related by the people involved. Where the interviewees felt it appropriate, some context is given but there is no political dimension. Clearly, readers will have their own opinions about our activities in Iraq and Afghanistan, and I am sure the service personnel have theirs. I asked for and received no hint as to what these might be. They were, and are, professionals to their fingertips and bootlaces. ‘We go where we’re sent,’ said one soldier, who might have been speaking for them all. ‘It’s not for me to question why I’m there. I get paid to do a job and I do it to the best of my ability.’

Of course, the Army are not the only armed service involved in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy (through the Royal Marines) have also done, and continue to do, sterling work. Thus, though inevitably the bulk of the stories herein are from the Army (including the TA), those services are represented, too.

I am grateful to the Ministry of Defence and its staff – particularly Tony Matthews, Alya al-Khatib and Major Tim David – for the assistance rendered in locating and contacting interviewees and in ensuring the requirements of operational and personal security were met. Memories of events which happened under stressful conditions some years ago are inevitably clouded; we have done all we can to ensure the accuracy of these stories, and Tony, Alya and Tim helped with this, also. There was no censorship by the MoD.

Above all, I am grateful to all of the interviewees for giving me their time. My name is on the front cover of this book only because someone’s had to be; all I did was sit and listen and then edit, as sparingly as possible, their words. This book is by them.

In modern Britain, for the last 60 years at least, we have been fortunate in living without the horror of total, all-consuming war. We have no conscription or national service, our armed services seem more remote than once they did and our eyes have turned inwards. But as you read the words that follow, I hope you will remember that some of our people are living different lives to yours. I hope they make you feel proud.